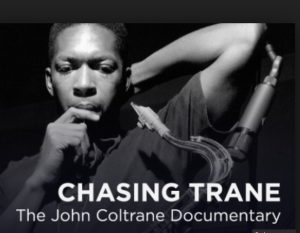

An Interview with John Scheinfeld, Writer and Director of Chasing Trane, The New John Coltrane Documentary

Some of you may recall that I had a bad reaction to the election in November and had a bit of a breakdown, totally justified as subsequent events would have it. One thing that helped me through the worst of it was going to the Doc NYC festival and seeing a new John Coltrane documentary called “Chasing Trane.” It was a beautiful and inspirational film that helped me heal and even sent me on a more spiritual path, which surprised the hell out of me. Here’s the original essay I posted on Nov. 25: “Chasing Trane: A Review, An Appreciation, A Spiritual Awakening.”

Some of you may recall that I had a bad reaction to the election in November and had a bit of a breakdown, totally justified as subsequent events would have it. One thing that helped me through the worst of it was going to the Doc NYC festival and seeing a new John Coltrane documentary called “Chasing Trane.” It was a beautiful and inspirational film that helped me heal and even sent me on a more spiritual path, which surprised the hell out of me. Here’s the original essay I posted on Nov. 25: “Chasing Trane: A Review, An Appreciation, A Spiritual Awakening.”

The essay found its way to the writer and director of “Chasing Trane,” John Scheinfeld, who sent me a lovely follow-up note telling me that he had shared the piece with many people, including Bill Clinton. He even used the word: “Bravo.” I was quite thrilled. Now “Chasing Trane” is set to make it’s theatrical release: It opens this Friday at the IFC Center in New York and the following week in Los Angeles, followed by a broader release across the country. I can’t wait to see it again and I’m strongly encouraging all of you to see it as soon as you get the chance.

In anticipation of the rollout, the film’s publicists reached out to see if I would be interested in doing an interview with Scheinfeld. Of course. So we did call a couple of weeks ago. It was supposed to be 20 minutes but it lasted 40. Scheinfeld was eloquent and passionate and it was exciting for me to learn about the creative process that went into making this wonderful tribute to one of my heroes. A summary of our conversation follows. All direct quotes are Scheinfeld’s.

Why Coltrane?

Scheinfeld had known about Coltrane, worked on a radio station in college and “like many people” was introduced to Coltrane through “My Favorite Things.” “I knew his music, but I was not an obsessed fan.” Scheinfeld has done documentaries on musicians such as Harry Nilsson and John Lennon and one of his producers approached him with the idea of doing a documentary on Coltrane.

“The more I looked into his story, the more I become intrigued and fascinated. We’ve seen the clichéd stories: an artist comes from nowhere, gets fame and money, abuses substances and dies a tragic death. Amy Winehouse, for example. Coltrane was the antithesis. He had similar challenges, but he did the right thing and overcame them and became John Coltrane. To me it was an uplifting and inspiring story. I said, ‘Yes, let’s do it.’ The first thing we did was put together an arrangement with the three record labels that own Coltrane’s music, so we would have access to all of the recordings. Then we made an arrangement with the Coltrane family. With those two pieces in place, I felt I could tell a story worthy of a remarkable artist.”

Process

One of the things that moved me about the film was the way Scheinfeld put Coltrane at a crossroads in his life in 1957: He had just been fired by Miles Davis and could either quit heroin or go the path of Charlie Parker. Coltrane quit cold turkey and, from that point on embarked on a decade of creativity and exploration that was perhaps unprecedented. I asked Scheinfeld if he went into the process planning to use that as a framing device.

“I did not go into it with the dramatic structure in place. But I knew I didn’t want to do a straight-ahead biography. If you look at many of the films I’ve made I often have a three-act dramatic structure. It is never he was born, he did this, he died. It comes out of my background as a scriptwriter: I come at it in terms of telling the story from a dramatic standpoint. I did know that I wanted this to be a portrait of an artist and not an analysis of his music. Rather than a straight-ahead bio pic, I wanted to focus on the critical events, the passions, the experiences that shaped his life. We have really focused on the man and not the music, but the music is certainly in there, 48 tracks, covering the full array of Coltrane’s revolutionary sound.”

How did the dramatic structure come about?

“It was only later, when I talked to more people who actually knew Coltrane, who knew him as a young man, knew the challenges he faced, including the addiction. That’s when the dramatic structure came to me. I watched far too many movies growing up and one of my favorite filmmakers was Frank Capra. One of the things he did so well was to take a regular guy and confront him with challenges to such a degree that he finds himself in deep trouble. A lot of where Coltrane eventually went was because of the situation he found himself in. Putting your hero at that kind of crisis point is a good way to draw in the audience.”

I mentioned to Scheinfeld that after seeing the film, I spent a lot of time listening to Coltrane – let’s face it, I always spend a lot of time listening to Coltrane – but this time with a deeper awareness of this demarcation period in his life, starting with the Prestige album Coltrane, his first album as a leader. His progression from there is really remarkable and, fortunately, we have the albums to follow his path of exploration, innovation and, often, sheer beauty. Scheinfeld said this was no accident.

“He said it himself. After he stopped all of that, he said he wrote better and he played better. People think they can be more creative by injecting with a substance. It’s a myth. One of the many lessons of Coltrane’s life that we see in ‘Chasing Trane’ is that when he got off the substances he became really great.”

Surprises?

I asked Scheinfeld if there were any major surprises in the making of “Chasing Trane.”

“Having done the research, I had a handle on the overall trajectory of his life and the moments that seemed of importance. Everything I learned was in support of what I had learned. One thing was how much everyone who knew him loved him. Another, that he was a person of quiet strength.”

How about the audience response to the film? Any surprises?

“I have really been warmed by the response of journalists and critics and by the audiences when we’ve shown ‘Chasing Trane’ at the various film festivals. There’s something about this film—and it’s probably best left to others to describe why—that is touching people and hitting people in a strong way. We’re opening in New York on April 14 at the IFC for at least two weeks, and longer if we perform well. Then on April 21 we open in LA. From there we will be on 50-plus screens and the number keeps growing every day. For a documentary, that’s great. The film speaks to people in some important way, and I am really confident it will inspire and uplift them in ways that are essential in today’s world.”

Speaking of Today’s World

Ah, today’s world. It was, after all, my reaction to the election and the uplifting effect of “Chasing Trane” that led me to write that first essay, which led to this interview. There is a terrific passage in the film where Coltrane’s song “Alabama” is played against scenes from the bombing in Birmingham where the four little girls were brutally murdered in their church. And also scenes from the atomic bomb blast in Nagasaki and a haunting image of Coltrane praying at the memorial.

So I asked Scheinfeld how he sees Coltrane’s legacy and the film in relation to what is going on in the world now. “From my point of view, the world changed with the election of the new president. It’s hard not to have this placed in front of you every single day when you turn on the news: The darkness, the dissent, the disagreement, the protests, a wide range of things that were not there before. The world is in a very different place, and I think it can be oppressive.

“People crave something more inspiring and uplifting, something that speaks to the best of human nature and not the worst. The life of Coltrane and our film speak to this. Because of the choices he made, he was able to transcend these difficulties and ascend into a unique place. Bill Clinton talks about this where he talks about the first time he heard ‘A Love Supreme’ and he says, ‘This is something to which everyone should aspire.’

“There is a very universal story about John Coltrane and his music whether you know him and his extraordinary body of work and love and admire him, or if you are just learning about him. There are aspects of his story that will really inspire you to follow your own dreams and not let anyone tell you want you can or can’t do.”

The “Chasing Trane” Legacy

I asked Scheinfeld about his goals for the film, not in terms of Oscars or money or adulation, but its impact

“I would hope that people will come and see the film and feel that they have seen a portrait of a remarkable artist. Not a jazz artist, and not a jazz film. I’m inspired by Coltrane’s words as spoken by Denzel Washington in the film. He said, ‘I don’t recognize the word ‘Jazz.’ I just feel I play John Coltrane.’ To me that says it all, a unique artist with a unique sound that transcends all attempts to pigeonhole him. I would love for people to look at this enormously talented artist who found success on his own terms, not for the money, not for the fame – although those came to him – but as someone who followed his art where it took him. That is to be respected and admired.”

The Music

At this point I had more than used up my allotted time with Scheinfeld and I was pleased with the ground that we had covered. Then I did what I have always done from my first days as a journalist. I closed with the open-ended question: Is there anything else you would like to talk about that we haven’t discussed. It turned at that there was and, in fact, Scheinfeld was extremely eager to talk about it, specifically for the audience here at Jazz Collector.

“I want to talk about how we used music in the film. There are nearly 50 Coltrane recordings, which is an impressive number for any documentary. We decided to approach the music not as a history lesson in his music, but like this; as if John Coltrane were alive today and I went to him and said, ‘I want you so score this film, taking pieces that you know and putting just the right piece of music in the right place in the film, underscoring the emotion, the feelings, the story point.’ His body of work is so amazing, we found every color, every texture, every mood, every tone that we needed to help tell the story.

“It is virtually wall-to-wall Coltrane music and it fits any moment in the script: The sadness of all the men dying in his life; the humor of Benny Golson and John Coltrane meeting for the first time; the challenges involved in kicking his addiction – we found the perfect piece of music to go there. He’s scoring his own life. My editor, Peter Lynch, has a real talent for putting the right music in the right place. Even those intimately familiar with the music will often hear and appreciate something new and exciting.”

I recalled at least three times in the film where I welled up with tears: The “Alabama” sequence, the first notes of “A Love Supreme” and the use of “After the Rain,” which I had thought was a recurring theme because it was used to such great effect.

“We used ‘After the Rain’ right near the end to underscore his passing. With the music and the visual elements and some good story telling, you have a chance to really move people and impact people. I’m very excited for people across the country to see this film.”

Denzel

Scheinfeld wanted to make sure he covered one more point, about Denzel Washington and his role in making the film come alive.

“During his lifetime, Coltrane did no TV interviews. He did a few radio interviews, but the sound quality was not good enough to use. I wanted to bring him alive in a much more vital and vibrant way. Happily, he had done numerous print interviews during the height of his career. We wanted to take extracts from that to illuminate what he might have been thinking or feeling at a particular time, to help make him a three-dimensional human being in our film.

“Relentless optimist that I am, I decided to aim high and have these passages read by a movie star. I put a list of five actors and went to a casting director friend of mine named Vickie Thomas and said, ‘Will you help me with this?’ She took the list and said, ‘I don’t know. We’ll try.’ That was a Wednesday. On Saturday I get a text: ‘Denzel is in!’”

“I didn’t know if he was a Coltrane fan, but it turns out that he is. Vickie gives me his number but warns me that he never answers his phone. On Monday I call him and he answers the phone right away. I don’t know what to say, but I finally get it out and he says, ‘Oh, yes, I love Coltrane and this is very interesting to me. But one thing: I gotta see the film.’

“So I send him the film. Five days go by. I’m sure he hates it. Then he calls. No ‘hello, no how ya doin.’ The first thing out of his mouth: ‘It’s beautiful brother. When are you coming to Pittsburgh?’”

Washington was in Pittsburgh filming “Fences.” Scheinfeld flew to Pittsburgh to record him on one of his days off. “He couldn’t have been nicer and more professional – in addition to being the fine actor that we know he is. He had the script ready and knew exactly what he wanted to do with it, his interpretation of Coltrane. One of the reasons he was on the top of the list is that so many of the people described Coltrane as being a man of quiet strength. He didn’t talk a lot, but he was very strong. Denzel has played a lot of characters like that in his career. He totally understood and got Coltrane and he delivers an interpretation of Coltrane that truly elevates the overall experience of the film.”

I mentioned that when I was watching the film, I got the impression that Washington was actually talking to someone, thinking about what he was about to say, taking the time to put his words together carefully. Scheinfeld chuckled and told me one more story:

“Normally when there’s a voiceover there’s a stool and a music stand. On the music stand there is a script and a pair of headphones so the actor can hear himself. So Denzel comes into the studio and we start to talk a little bit. ‘I don’t want to do it that way,’ he says. ‘These are words he spoke to a journalist across a table. I’d like to sit at a table and imagine that journalist sitting before me.’ He wanted to be in that moment, imagining he’d been asked the question.”

Coda

We were now at the end. I told Scheinfeld once again how much I was moved by the film and how much I, as an ardent admirer of Coltrane for more than 40 years, appreciated his efforts in bringing Coltrane’s story to life and capturing the essence of the man and his art.

“As filmmakers, we sit in small dark editing rooms and we don’t know what we have until we show it to a room full of strangers. I’m so happy to hear that the film moved you. It’s what you hope to hear. I’m so proud of this film. I just want people to come out and see it.”

Wonderful interview, hope I can catch the film somewhere. This type of stuff doesn’t always find a way to play in Iowa

Curious about it for sure.

What I don’t understand is the statement that there aren’t quality audio interviews with Coltrane out there. I know of two: the Kofsky and the Japanese interview. They are both easily available and sound more than fine (and presumably could be cleaned up even more with contemporary technology). Could the director not get clearances to use them?

Abrasive_Beautiful Nice surprise to find another Iowan on the bored.

I’m hoping this release will either be on a streaming service or be available to download.

Hey very cool!

I’m in Iowa City. When Miles Ahead and Born To Be Blue came out, the jazz station KCCK hosted a double feature at the indie theater. I’m hoping they can arrange a similar event, and I did suggest it to them a few months back. I have no idea the process to get a film screened, but maybe worth another email.

I hope this comes to an art house in London soon..?

BTW does anyone have news on the Moondog Film which was in production but seems to have

vanished?

Saw it Saturday. Wasn’t too impressed — the director actually introduced the film and did not talk about Coltrane, only about how he got Denzel to do a few voiceovers. He seemed like someone I would not want to spend more than 2 minutes talking to.

I had a lot of problems with the film’s organization and my girlfriend, who’s not really a jazz nut, found the organization difficult to follow and had also wished for Coltrane’s voice to be included (to me it’s clear that Scheinfeld wanted a specific actor’s voice, whether or not Trane interviews could be cleaned up). Clinton seems like another weird choice — where was Pharoah? Where were some of the jazz musicians he influenced, like Gary Bartz or Archie Shepp? Santana and Densmore are cool but come on… And as great as Coltrane was, he was one musician in a pretty vast setting, which is not clear from the film. Jazz is a whole lot more than Miles, Monk, Parker and Coltrane and even if one is doing a film about a single individual, one has to give an idea that there was some other stuff occurring in the music after 1949.