The Complete Jazz Collector Irving Kalus Collection

I was doing a search on Jazz Collector to refer to the Irving Kalus Collection I purchased in 2012 and realized I never put the entire story together in one post. In re-reading this for the first time in years, my own story-telling is fine and fun, but I must admit that Irving’s own article about Bird at the end is the real gem here. Without further ado:

I was doing a search on Jazz Collector to refer to the Irving Kalus Collection I purchased in 2012 and realized I never put the entire story together in one post. In re-reading this for the first time in years, my own story-telling is fine and fun, but I must admit that Irving’s own article about Bird at the end is the real gem here. Without further ado:

So I mentioned the other day that I recently purchased a record collection. Here is the story.

A few weeks ago a woman sent me the following e-mail: “I’m wondering if you can help me. My dad passed away suddenly in an accident. He left a huge jazz collection of approximately 2500+ vinyl albums. He died at 82 and was a jazz enthusiastic since his teens and his collection dates back to then. To his great disappointment I did not share his passion for jazz. I am interested in selling his collection. How can I go about finding its value? I’ve read some of the information on your blog and realize I need to consult an expert. Any guidance you can give would be greatly appreciated.”

I get emails like this fairly often now that I do Jazz Collector. They usually don’t turn out to be much. I generally look to help people over e-mail and my advice if they have anything collectible is to usually tell them to try to sell the records on eBay. I’m not necessarily looking to purchase collections: I’m still a collector and not a dealer and I have way more records than I have places to keep them. Some of you, Rudolf I’m sure, may even recall that I began a project several years ago to pare down my collection, which I grandly labeled The Great Jazz Vinyl Countdown. Needless to say that project is quite defunct.

I do enjoy helping people and sharing my knowledge, which is one of the reasons I love doing Jazz Collector, and I also continue to keep an eye out for interesting collections. So I did what I normally do when I get an inquiry like this, which is to first try to figure out if the records have any value. I wrote back and suggested that she look through the records and pull out any Blue Notes, Prestiges or Verves and let me know some of the titles, so I could get a sense of what she might have. Oh, and I also asked where the records were located. I figured if the records were convenient to either of my homes in New York or Massachusetts I could always stop by and take a look.

A few days later she wrote back with a list of records. She said she went through about 100 records. There was one Blue Note – Jazz Classics, Celestial Express, the Edmond Hall Celeste Quintet. There were two Prestiges – Bean and the Boys, a Coleman Hawkins reissue, and the Walter “Foots” Thomas All Stars, which, honestly, I had never heard of. There were several Verves, which consisted of a few Roy Eldridge records and a JATP record. I wrote back and asked if any of the Verves had a drawing of a trumpeter on the label. She wrote back and said they could not locate a drawing of a trumpet player on any of the labels I mentioned.

Based on the evidence at hand, I figured, eh, not a collection worth pursuing, at least not for me. It didn’t seem like a collection with original pressings and it seemed to tilt more towards more traditional jazz as opposed to the bop and hard bop of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the jazz that most of us here at Jazz Collector love and crave. If the records hadn’t been at a convenient location, I probably would have just passed up the opportunity and told her to look on eBay to see if she could find comparable records to see if hers had any value.

But she told me the records were located in Massapequa, which is in my old stomping grounds – and record-hunting grounds. When she gave me the address I realized the records were literally around the corner from my favorite record store, Infinity Records. At this point I really assumed the collection was nothing special – if it was anything special, surely my friend Joey at Infinity would have gobbled them up by now. However, it was Massapequa and I was planning to drive from The Berkshires to Long Island with The Lovely Mrs. JC on the following Monday, and I figured I could take a look and then, worse comes to worse, stop in and say hi to Joey at Infinity.

So I set up a time to see the records.

So it came to that Monday, June 25, and I was driving down from The Berkshires to drop The Lovely Mrs. JC off at her office in Great Neck and I was then to head out to Massapequa to see this record collection. And I really had no expectations about the collection and no real desire to see it and was feeling I was doing it just as a favor to the woman who sent me the e-mail to help her out because, clearly, her father loved jazz and it would be a nice thing to do. So I told The Lovely Mrs. JC, who tends to get nervous when I am around too many records, that there was nothing to worry about, that it was not a collectible collection and I would just take a look at it and give them advice and not be bringing any more records home. No problem, I said, but the look in her eyes was a familiar combination of doubt and dread.

I got to the house in Massapequa at the appointed time, put my dog Marty in a carrying bag and was greeted at the door by a muscular young man who let me in and told me his name was Adam and it was his grandfather’s collection. And then Adam’s mother appeared, and she was the one I had been e-mailing with, and introduced herself as Karen. I assumed Adam was there to ensure that I wasn’t some wacked out crazed record collecting nut, which seemed like a reasonable expectation at the time, and I thought this was a wise decision on their behalf. Karen appeared to be a few years younger than me, but of my generation, and we started chatting and we had a very nice rapport because we had in common, among other things, fathers who were obsessed with jazz music and jazz records.

After chatting for a few minutes I said I was ready to see the records and Karen and Adam led me into a room towards the back of the house. In the room were four distinct record cabinets, one on each wall. I put Marty’s carrying bag on the floor and completely bypassed the cabinet to my left, not even looking at it, and went straight ahead to the largest cabinet, the one directly in front of me, because it was not only the largest of all the cabinets but it contained several records with the familiar orange and black, thick spine of the Impulse label. And when I saw the Impulses I had some hope that, perhaps, there were records of interest to me in this collection.

I went right over to the Impulses and pulled them out. They were all Coleman Hawkins. I looked at the labels: Orange. Good sign. Also, the records were in immaculate condition. On the same shelf there were a bunch more Hawkins records, mostly reissues. But it was a start. I took a glance down. Aha, I thought, the records are in alphabetical order and in the shelves under the Hawkins records were the M’s, meaning Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Jackie McLean. If there were to be original Blue Notes or Prestiges, now we were cooking.

I bent down. Found the Mobleys. Oh, goodness: Every single 1500 Blue Note. My heart began racing. I pulled out the first one: Blue Note 1568. But as soon as I felt it I knew it wasn’t an original. It was just too thin. I looked at the back: Toshiba-EMI. A Japanese pressing. I pulled out all of the other Mobley Blue Notes. Same story. Either Japanese or United Artists. Lee Morgan, same deal. Jackie McLean, same deal: All great records, all great music, but, alas, no original pressings, nothing of any value to a collector of originals, which I am. Then I looked back up: Billie Holiday Verves. I pulled them off the shelf: Each one an MGM pressing. I looked down: Ben Webster and Lester Young Verves. Each one an MGM pressing. Not a single original in the bunch.

I started thinking: If this guy was collecting from the 1950s, why didn’t he have more original pressings. Then it hit me: Red Carraro. All of the records here I had basically seen in the same form at Red Carraro’s house – the MGM Verves, the UA Blue Notes, they all came from Red. I even saw on the back of some of the records the familiar handwriting of Red, in the upper left corner on the back, in pencil, describing the condition of the records. It was possible that the owner of these records had done what other collectors had done: Trading original pressings to Red and getting 2-3 later pressings in return. I also figured if the owner of these records dealt with Red, at some point we might have crossed paths.

Then Karen came into the room to check on my progress and to tell me something she had just remembered: Her father used to deal with some guy, buying and selling and trading records. She didn’t know his last name, but she heard her father refer to him as “Red.” Now the collection was starting to make sense: A collection of great music, great records, great artists, but not a collection of significant monetary value to me or to any collector or dealer because it was not a collection filled with original pressings.

Then I glanced over to the other side of the room, at the cabinet I bypassed on my way in. And from across the way, I could see even more Impulses, and they were all together on one shelf and there were at least a dozen of them and I knew in an instant what they were: They were the Coltranes. And I said to Karen that I hadn’t really found any records of significant value yet, but there was a ton of great music and great artists and her father had great taste in music and I’d like to keep on looking. And she said sure and walked out and then I crawled across the floor over to the other side of the room and grabbed at the Coltrane Impulses.

So I’m sitting on the floor and there’s this two-shelf low cabinet and there’s maybe 300 records in it altogether and I reach for the Coltranes on Impulse and pull them out. They are not obvious originals but each one has a gatefold cover, so there is hope. I open the first one, Ballads. And it is . . . ugh, a very late black label pressing. Then A Love Supreme: late pressing, black and red label. In fact, I go through all of the Coltrane Impulses and there’s not a single original pressing in the bunch. And now I’m fairly convinced that this is just a lovely collection of great music but not one of collectible records. And I am almost ready to give up and give Karen my advice, which is that she should probably go to Infinity Records around the corner and see what they would pay.

And then, in the middle of the Coltranes, there is this record: Sonny Clark, Sonny’s Crib, Blue Note 1576. And I remember thinking, why is the Sonny Clark record amid all of the Coltranes? But, of course, Coltrane is a sideman on this record and if the guy was a real Coltrane fan perhaps he organized his records according to his favorite artists and wanted all of his Coltrane records in one place. As a collector who constantly reorganizes and plays with my own collection, I could certainly relate to that.

So I pulled out the Sonny Clark record and took the record out of the sleeve and I was absolutely sure it was just like all of the Blue Notes on the other side of the room, probably a United Artists pressing or a Japanese reissue. And I glanced at the label and slid the record back into the sleeve, barely looking at it, assuming it was like the rest. But something registered. I slid it out again: Blue Note Records, 47 West 63rd, NYC. There were deep grooves, RVG and the ear. Could it be? An original pressing of Sonny’s Crib? And I looked at it again, and again, and again. It was indeed an original. Among all of these other reissues, here was an original pressing of Sonny’s Crib. And I knew this was a record of value and, more of interest to me as a collector, it was a record I did not own, at least not as an original pressing.

So I kept looking on these two shelves and there were more records of interest: Original pressings of records from Coltrane and Miles Davis and Clifford Brown and Sonny Rollins and Bud Powell and Charlie Parker. Among these were records on the Prestige and Blue Note labels and everything seemed to be in very nice condition. These must have been the guy’s favorite artists, I thought. These were the only ones he cared about in terms of having original pressings. This guy was a discerning collector, I realized, and had pretty much the exact same taste in music as me. I mean, if I were to list my favorite artists these would be the exact same players, with the probable addition of Thelonious Monk, who was surprisingly not well represented in this collection.

So now I am sitting on the floor, Marty the dog still quiet in his crate, and I am thinking that this is quite an interesting collection and I have no idea what Karen really wants to do with it and whether it would be something I’d be interested in buying. But I know that I promised Karen I would tell her if there was anything of value in the collection so that she could make an honest assessment of what to do with it. So I got up, left Marty behind to guard the records, and found Karen and Adam sitting in the living room.

So now I had a general sense of the collection but since my original intent was to just look it over and give advice, I had no real sense of whether I would want to buy the collection or even whether they would be interested in selling it to me. So I wasn’t overly excited or enthused as I sat down with Karen and Adam to tell them what I had discovered. I said that it was an amazing collection of music mostly from the bop and post-bop era, that most of the records were reissues or later pressings, but that there were, indeed, some valuable records within the collection.

I didn’t say how many valuable records because I had no idea. I then asked Karen if her father had ever talked about the records and what they might be worth and what to do with them after he passed away. She said that she had never really had that discussion with her father, and neither did her brother. She said her father just loved the music and never really considered the records as something of monetary value, just something to treasure and enjoy.

I asked what they wanted to do with the records. She said they – she and her brother – probably wanted to sell them, but the only firm offer they had received was from a local dealer and it wasn’t anything near what they had hoped to get. She said if all they were worth was the price the local dealer offered, they would probably choose to keep them and eventually donate them. I figured the local dealer was Infinity, so I asked: It was, although it wasn’t Joey that looked at the records but one of the young workers in his store. I guessed that the offer was probably about $1 a record, but I didn’t ask directly. Instead, I repeated that there were definitely some valuable records in the collection and the best way to get the best value would be to try to identify the rare records through my Web site at Jazz Collector and then sell those records individually on eBay.

Neither Karen nor her son Adam looked particularly enthused about the idea of poring through each record and trying to figure out if it was collectible and then setting up a site to sell the records one by one on eBay. I watched their reaction and then out of nowhere I heard the following words blurt out of my mouth:

“If you would want to sell the whole collection, I would probably be interested in buying the whole thing.”

I could see right away they were interested. Then, again without thinking, I blurted out a number. It was a number without any real pre-ordained thought, but a number that was fueled by the intoxicating impact of just having held a clean original copy of Sonny’s Crib in my hands for the first time in my life and knowing that with the right number this record could be mine. There were something on the order of 3,000 records in the room and I was offering to buy all of them to get one. It was pure emotion and adrenaline and I was completely winging it at this point.

“Is that a firm number?” Adam asked.

“I think so,” I said.

Then I thought about it for another second.

“You know” I said, “let me look at the records for a few more minutes and I’ll tell you for sure.”

So I went back into the room with the records. I’d forgotten all about Marty the dog, who was still waiting patiently in his carrying bag. I went immediately back to the shelf where Sonny’s Crib and the Coltrane and Miles records were sitting and I started pulling records off the shelf. I looked at each one, checked to make sure the cover was original, pulled out the vinyl, looked at each label, felt to see if there were deep grooves, looked for the appropriate RVGs and ears. I must have pulled out about 40 original pressings. I never even looked at the other two shelves on the other sides of the room to see what was there. I thought to myself, do these 40 records along with the other later pressings Blue Notes and Verves justify the offer I had just made if, worse came to worse, I had to sell them all on eBay? The answer was a definite maybe. But there was Sonny’s Crib and the emotion took hold again and I went back into the other room and told Karen and Adam that, yes, this was a firm offer.

Karen said she was inclined to sell them to me and said she would talk it over with her brother and let me know as soon as possible, probably the next day. I smiled, thanked them both, packed up Marty and left the house thinking to myself: “Did I really do that? Did I really offer to buy this entire collection? What if they say yes? Where will I get the money?”

And then reality set in. The real unavoidable, inevitable, unenviable reality of realities: What would I tell The Lovely Mrs. JC?

Have I ever mentioned that The Lovely Mrs. JC is a psychotherapist by profession? You’d think after 35 years of marriage to a shrink I’d have been somewhat cured of my vinyl obsession by now. Anyway, The Lovely Mrs. JC returned home from her practice that Monday evening and we sat down to have a quiet dinner and chat. We had many things to talk about and the record collection wasn’t foremost on her mind and, in fact, I had made such little light of the prospects for this collection that it seemed to have slipped her mind completely. So I had to bring it up.

Have I ever mentioned that The Lovely Mrs. JC is a psychotherapist by profession? You’d think after 35 years of marriage to a shrink I’d have been somewhat cured of my vinyl obsession by now. Anyway, The Lovely Mrs. JC returned home from her practice that Monday evening and we sat down to have a quiet dinner and chat. We had many things to talk about and the record collection wasn’t foremost on her mind and, in fact, I had made such little light of the prospects for this collection that it seemed to have slipped her mind completely. So I had to bring it up.

“You know I saw that record collection today,” I said, quite casually.

“Oh, yeah,” she said. “Anything of interest?”

“Yes, it was pretty interesting,” I said.

We sat in silence for a few seconds.

“There’s a chance I may be buying it,” I finally said.

She stared at me in stunned disbelief.

“How many?”

I smiled a sheepish smile and held up three fingers.

Her eyes popped out of her head. “Three hundred records! How can you buy three hundred more records!”

I shook my head no. I said it wasn’t three hundred. She smiled a smile of instant relief.

“Three records. That’s fine.”

I shook my head no again.

Her face turned an ashen white. She pushed the words out softly, as if they were pure evil and should have never been voiced aloud by any human being.

“Three thousand records.” It was barely a whisper.

The words just sat there between us. Her face went from white to green. She looked physically ill. She couldn’t swallow and her breathing tightened markedly.

“You’re not serious, are you?”

Now I should explain something, lest you reach the mistaken conclusion that The Lovely Mrs. JC is anything but a wonderful and supportive spouse. About a year ago we decided to sell our home in Great Neck and downsize and get rid of many, many things that were deemed unessential. The Lovely Mrs. JC rid herself of hundreds of books and some artwork that she had treasured and I vowed to shrink my record collection, not only through the now mythical Great Jazz Vinyl Countdown, but through selling records on eBay and even donating records to charity. Last year, in fact, I sold 500 records at a garage sale for $1 apiece and donated 1,500 more to the ARChive of Contemporary Music. This was huge progress in the interest of matrimonial compromise and bliss.

However, since then I had done nothing to downsize and, in fact, had purchased two more collections and had custom cabinets built in our Berkshires home to accommodate several thousand records. In fact, I had recently designed new cabinets with my builder that were to be installed the following week, allowing me to get records out of storage and have space for yet another full roomful of records on the order of at least 2,500 or so.

As the color of her face went from white to green to white again and then starting recapturing its normal pinkish hue, The Lovely Mrs. JC asked me what I intended to do with these 3,000 records. I didn’t have the heart to tell her that it was really about 50 or so records that I cherished, that I wasn’t even sure what was in the entire collection. But I had thought about what to do with the records and it was a strange conclusion I had drawn that was completely unexpected to me. I wanted to keep the collection intact for a while, to just have it and pore through it and play with it and play the records, without thought to whether or how or when to sell the duplicates. For some odd reason I felt respectful to the owner of the records, whom I had probably never even met, and wanted to honor him in some way by keeping his collection alive. I have a feeling it had something to do with my own father, who passed away about 15 years ago: Knowing how much my dad treasured his records and how much it meant to him to build up his own collection and how each record he purchased meant something special to him. It seemed kind of odd, but for some reason felt natural. It was what I would have wanted for my own dad, I guess. In any case, The Lovely Mrs. JC was suddenly sympathetic to the situation.

“You know those record shelves you are building in the country,” she said. “If you buy the collection, you could put the records there.”

Brilliant. Hadn’t even thought of it myself.

So the potential obstacle of The Lovely Mrs. JC was now overcome and her support was in hand. And now I knew what I would be doing with the records if I were to purchase them. Next I just needed to get the OK from the owners of the records. Which turned out to be not as easy as it may have seemed.

When I left Massapequa on Monday Karen said she wanted to sell the records to me but it was not her decision alone, she would have to consult with her brother. She believed that he would also want to sell the records to me and they’d probably give me the go-ahead on Tuesday.

When I didn’t hear from Karen by Tuesday evening I started getting a little nervous: Were they getting cold feet, were they shopping the collection around, was there suddenly going to be a slew of cutthroat record dealers sniping for the records? Just the normal paranoia, right? I wasn’t all that concerned because I believed that no dealer would come close to the offer I made because, well, for me it wasn’t a business decision but an emotional decision. If it was about business, I would have spent more than a half hour with the records in the first place, and I would have at least gone through them all to identify the ones of the most value and to figure out how to get rid of the ones I didn’t want. But I was just improvising and by this point it wasn’t about whether I had made the right decision to buy the records, it was just about closing the deal.

I had sent Karen a note on Monday, telling her how much I enjoyed meeting her and seeing her dad’s collection. She replied late on Tuesday: “Hi, Al, I enjoyed meeting you, too. I would like to sell you dad’s collection. I spoke with my brother Gary and he wanted a day to think about it. I will be meeting Gary at the house tomorrow (Wed) and we’ll give you a call. – Karen.”

But I didn’t hear from Karen or Gary on Wednesday.

I called Karen on Wednesday evening. “Gary’s still not sure,” she said. “He wants to count the records. Hopefully we’ll have a decision by tomorrow.”

I could see it now, Sonny’s Crib slipping away forever.

The next afternoon I received a call from Gary. I hadn’t spoken to him yet. We talked for a while and it was clear he was a very sweet guy. He really just wanted to talk about his father and his dad’s love for jazz and his love for the records. I’m sure it was sad for Karen and Gary to be giving up the records: Even though they really didn’t have the same kind of appreciation for them as their father, they were such an important part of their dad’s life. It was like saying goodbye to him all over again. In a way, I think Gary wanted to feel they were going to someone who would truly enjoy them. I assured him that would be me.

In any case, Gary had counted the records and the final tally, he said, was 2,345, counting all of the individual records in the collection, where a double record would count as two. This made me feel a little better: At least it wasn’t 3,000. We discussed the price and quickly came to an agreement. The deal was in place. The records were mine. I just had to pay for them and pick them up.

Gary and I arranged for a Saturday pickup in Massapequa and I recruited my friend and business partner Mike to help. Mike is not only strong, he has a big car. I got to the house at about 9:30 on Saturday morning armed with 25 empty record boxes and several empty crates. I went to the back room where the records were located. It was 90 degrees outside and there was no air conditioning. I was undeterred, running on pure adrenaline. I opened a box and a crate and went immediately to the cabinet where all the original pressings were located.

This was my plan: I would go quickly through the records – anything that looked like a rare collectible I would put in a crate; anything that was not a collectible would go in a box. The boxes would go directly into storage, the crates would come with me back to Manhattan for inspection, perusal, heavy petting and listening. There was no way I was bringing home 25 boxes and two crates of records. The sight alone would have thrown The Lovely Mrs. JC over the edge. Eventually everything would end up in The Berkshires on my new shelves.

By the time Mike got there at 10:30, I had already loaded about 15 boxes and more than half a crate. Mike started loading them in the car. It was now 92 degrees. In the end, there were 27 boxes and two crates. The 27 boxes went into Mike’s SUV, the two crates went into my Prius. We drove off in the two cars and I breathed a deep, deep breath. The records were mine. Sonny’s Crib, the Miles Prestiges, the Bud Powell Blue Notes, and all the rest, some I will treasure forever, some I have no idea what I will do with.

Eventually I made my way back to Manhattan and put the two crates on a cart and up the elevator and into my apartment. I put them on a table and flipped through them one by one. I pulled one out to listen: Clifford Brown and Max Roach, Emarcy 30036, side two, Daahoud, Joy Spring, Jordu, What Am I Here For. I put the record on the turntable and sat back on the sofa in the living room, clutching the cover in my hand. This, indeed, was heaven.

Part 7 – In Memory of a Jazz Collector, Posted July 26, 2012

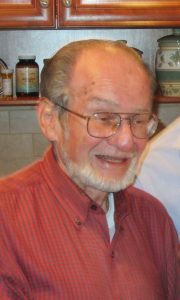

Irving Kalus was 82 years old when he died on December 22, 2011. It was early in the evening and he had just gone to the record store around the corner, Infinity Records, in Massapequa Park on Long Island. He bought a Miles Davis record and was crossing Sunrise Highway when he got hit by a car and was killed instantly. I didn’t know Irving Kalus personally, but I seem to know him quite intimately now, at least in connection with one particularly important area of his life: His love of jazz. It was Irving Kalus’ collection that I purchased a few weeks ago and I would like to share what I have learned about the man and his life-long passion for jazz.

Irving fell in love with jazz when he was a teenager. His son Gary remembers him telling stories about musicians he had met – the time Sarah Vaughan kissed him on the cheek, the times Dizzy Gillespie would talk with him outside a club before or after a gig. Bud Powell once fixed him a drink: “He called it a Joe Louis because he said it will really knock you out,” Gary recalls his father telling him. Irving picked up on bebop quite early and it clearly had a profound influence on his life.

In 1949, when he was just 20 years old and bebop was still in its early years, he wrote a thoughtful, compelling and heartfelt tribute to Charlie Parker for an advanced composition class at New York University. He titled the paper “Ornithology” and he kept it all of these years. He was proud of it, appropriately so. After I purchased the collection his daughter Karen gave me a copy. I was moved by several things, particularly the quality of the writing, the advanced ideas Irving expressed and his awareness of the impact that Bird would have on music, even at that early date. The paper included some direct quotes from Bird, some of which I had never seen before, and I wondered if perhaps Irving had spoken to Bird himself.

The other thing that really struck be about the paper: Not only that Irving saved it all of these years, and that Karen and Gary saved it, but the date on the paper: December 22, 1949, the same day that Irving died 62 years later. A little eerie, no? Anyway, I will post the paper in full tomorrow.

There is something oddly intimate about going through someone else’s collection. I could see how he organized his records, which musicians were his favorites, which records were most precious to him. Even though we never met, I could tell you in intricate detail about his taste in music. Rather than finding the experience ghoulish, I’ve actually found it quite reassuring: In some ways it’s like a final act of sharing, one collector to another, one fan to another. It helps that we loved the same music, the same records and the same artists.

I feel like a curator keeping the collection alive for a little longer and it’s hard not to think about my own father at the same time, trying to keep him alive as well. My dad also loved jazz, loved collecting records, loved listening to and talking about jazz. He and Irving were of the same generation and there’s a connection that’s hard to ignore. If you think about the jazz fans of that era, born in the 1920s and coming of age during the bebop revolution, you realize that most of the people who experienced it are not with us anymore. I was two years old when Charlie Parker died. Irving was 26, my dad was 29. They saw him live on 52nd Street, and they saw Art Tatum and Fats Navarro and Clifford Brown. We will soon reach a time when people who were actually there at the conception of the music we love will no longer be around to tell us about it. And that will be a sad day.

As for the collection itself, Irving had it all. More than 100 Blue Notes from the 1500 and 4000 series, early Prestiges, many of the records we talk about here at Jazz Collector, signifying the best of the bop and post-bop eras. The interesting thing was: He didn’t seem to care whether he had original pressings of most of the records: As I mentioned in an earlier post, he had all of the Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley and Jackie McLean Blue Notes, but not an original pressing in the bunch. Same with Dexter Gordon, Horace Silver, Lou Donaldson and other artists. So I now have in my home in The Berkshires a sizeable collection of later-pressing Blue Notes, ranging from Liberties to United Artists to Japanese pressings.

There were, however, some artists that were clearly more important to Irving, and he had a separate cabinet for these artists, not in alphabetical order, just a cabinet unto itself. These were: Clifford Brown, Sonny Rollins, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Fats Navarro. It was in this cabinet that Irving housed his most precious records and the ones that clearly meant the most to him. There were original pressings on the Blue Note, Emarcy, Savoy, Riverside and Prestige labels by all of these artists. Irving wasn’t obsessive in the sense that he had to have an original pressing of each record – but where he had an original pressing, it was in pristine condition. Obviously, this is what attracted me to the collection, and why I risked the potential wrath of The Lovely Mrs. JC to pursue it.

I can also tell you that Irving was loved by his children, who spoke warmly of him in all of our interactions and treated his passion for jazz with utmost respect. Karen said she remembers times when her father would help her with writing – “he was a wonderful writer,” she said – and she would go downstairs to the basement in their old home and he was always listening to his records. “That was when he was at his most relaxed.” Every Friday evening at the end of the workweek, Irving would trek from Brooklyn into Manhattan in search of records.

Gary remembers how much his father loved the music and would share his love of music with anyone he respected. He told me about one time walking in the city with his dad when a man came up to Irving and gave him a big bear hug. “He thanked him for something, I don’t know exactly what, but you could see he liked my dad very much and was very warm to him,” Gary recalled. “When he walked away my dad said he was Sonny Rollins’ cousin and my dad couldn’t even remember what he had done for him. He was just like that.”

It’s odd that I never met Irving because we traveled in the same circles. Perhaps I had seen him at Infinity Records, or at Red Carraro’s house, or at one of the many record shows in New York or Long Island. If we had met under those circumstances perhaps we would have looked at one another suspiciously – competition for the few precious gems we were both seeking. In the end, however, we both shared a bond in our love for jazz, our love for music, our love for the records. And now we share one more thing: Irving’s record collection.

Rest in peace, Irving.

Part 8 – Guest Column: Ornithology, by Irving Kalus, Posted July 27, 2012

As promised, here is the paper written by Irving Kalus on Charlie Parker, dated December 22, 1949. I have to really admire that Irving caught on to bebop so quickly and ardently, and he recognized the genius and contribution of Bird. You can see that this paper is written with tremendous passion and feeling and probably some hyperbole that can be easily excused by the exuberance of youth. As Irving’s son Gary told me, Irving was a fan of Benny Goodman . . . well, read it and see.

I’ve reprinted the entire paper below and I’m also attaching it as a downloadable PDF (Ornithology). It’s remarkably similar to the article I wrote in 1975, when I was 22 and had the benefit of 20 years of history after Bird had died. You can find my article here: An Old Jazz Collector Tribute to Charlie Parker. Irving was neither a writer nor jazz critic by trade, but he certainly had a gift for both and, from now on, perhaps forever, whenever anyone does a Google search linking on Irving Kalus, the names Charlie Parker and Irving Kalus will be inextricably tied together. It’s a nice thought and a pretty apt tribute, wouldn’t you say?

Ornithology

By Irving Kalus

Paper submitted for Adv. Comp. class, Department of English, NYU

December 22, 1949

Fifty-Second Street was crowded that night late in April 1947. The crowd was composed, as it usually is on this particular New York street off Seventh Avenue, mostly of musicians. But the usual calm, stoical attitude of these men had changed that evening to one of eager excitement and almost nervous apprehension. A feeling of electrical tension was in the air and over the buzzing musicians and music-lovers and the anxious queries of passersby one could hear, “The Bird’s back in town.” From one club to another, from one bar to another the words had been whispered in sepulchral tones usually reserved for religious leaders and revolutionaries.

What manner of being could cause this kind of excitement? Who is the “Bird”? The “Bird” is a musician—a jazz musician. He plays the alto saxophone. His real name is Charlie Parker but the nickname “Bird”, whose origin even its owner can’t determine, is the one all musicians speaking of or to him, use. The following statements made by people in the jazz world are typical of the attitude of respect and even idolatry in which Charlie Parker is held:

“Bird is the greatest instrumentalist I’ve ever heard. He can express anything he can think of on his horn. And if he thinks of more than he plays then he’s even greater than we believe he is,” said Charlie Ventura, a fellow saxophonist.

“Bird is in a class completely by himself. The wonderful fluid continuity of his playing, the delicacy of his phrasing – his ideas make music,” said Freddy Wilson.

“I think Charlie has the greatest sense of time – the greatest feel of time. And his wealth of ideas. So different and so melodic. He thinks so much faster than anyone else – his music tells a story,” said Duke Ellington.

One of his disciples, a young, highly-regarded trumpet player said this of Bird:

“I studied at the Washington Conservatory and then at Julliard but I learned more from playing and talking to Charlie Parker.”

But another young musician, one who was performing in one of the nightclubs on Fifty-Second Street that anxious evening summed up the underlying feeling of the entire jazz world when he said:

“Bird has conquered the harshness of jazz and expressed pure beauty – his influence on our music and our lives is too great for me to define.”

All this enthusiasm elicited for a jazz musician may seem exaggerated or even ludicrous to those who have never really understood America’s greatest contribution to the Arts. We have come to regard this young struggling music form, through the commercially distorted views we get of it, as childish, faddish, unimportant and even offensive music. The word “jazz” has come to be regarded as synonymous with vulgarity and commercialism, and I cannot deny that this opinion is at least partially justified in lieu of the fact that what is heard of the music and referred to as jazz is usually at best no more than a gross caricature of a pure, moving, soulful and more recently an intelligently thoughtful art. Those who in their attempts “refine” the music and make it more palatable for public consumption have not only profited by squelching the young art but added to the popular misconceptions already formed.

To condemn the pimps and prostitutors of jazz such as the Paul Whitemans, George Gershwins and lesser lights like the Dorsey brothers, Harry James, and those half-sincere musicians like Benny Goodman and his ilk is not directly my purpose in writing this paper. My purpose is to bring to light a key figure in jazz, one who has been responsible for a revolution in the music – a revolution which began in the early nineteen-forties and whose scope and dimensions none of us were astute enough to predict at the time.

It has been the fortune of jazz to elude any and all attempts to tie it down, even to words. For better or for worse, the very name of this music has resisted any really satisfactory explanation. Often, when the whole can’t be defined, it is possible to make some sense out of it by summing up its parts. But when a part grows so big that it almost eclipses the whole, as Charlie Parker’s music has spurted beyond the confines of jazz, simple definition becomes utterly impossible and complex description must take its place. But complex description cannot and will not be understood by the lay public so the best that can be done is to give a brief biography of the man who raised jazz to a really thoughtful level, who gave it freshness, form and profundity, and to explain as adequately and yet as simply as possible how this rather awesome feat was accomplished.

The story begins on August 29, 1920 when Bird was born in Kansas City. He went through elementary school, spent three years in high school and would up a freshman. He played baritone horn in the school band and started seriously on the alto at the age of fifteen, when his mother bought him one.

Charlie was introduced to night life at its most lurid when he was still an immature lad of about fifteen. Basically he was not anti-social or morally bankrupt, but his true character was warped by contact with vicious elements in the Kansas City underworld, and his entire life and professional career have been colored both by these contacts and his background of insecurity and racial discrimination. The Bird is a Negro.

Charlie spent many years fighting an addiction which was wrecking his life. His dissipation began as early as 1932, taking a more serious turn in 1935 when an actor friend told him about a new “kick”. It was then that the addiction to marijuana, which, regardless of all misinformed statements to the contrary, is a fairly mild dope, gave way to the really nerve shattering and sometimes completely collapsing drug- heroin. One morning very soon afterwards he woke up sick and not knowing why. The panic, the eleven year panic was on. Eleven years were ripped from his life. As Bird once confessed in an informal interview:

“I didn’t know what hit me –it was so sudden. I was a victim of circumstances. High school kids don’t know any better. That way you can miss the most important years of your life, the years of possible creation. I don’t know how I made it through those years. I became bitter, hard, cold. I was always on a panic, couldn’t buy clothes or a good place to live. Finally, out on the coast I didn’t have any place to stay until somebody put me up in a converted garage. The mental strain was getting worse all the time. What made it worst of all was that nobody understood our kind of music out on the coast. They hated it. I can’t begin to tell you how I yearned for New York.”

Shortly afterwards Charlie went into the physical and mental decline that has become legendary in jazz history. But more on that later. First we will follow his career as a musician up to that almost fatal point. Charlie first went to work for a bandleader named Jay McShann who came to Kansas City in 1937. He left and rejoined this band a few times and gained some of his other early experience with local bands.

As early as 1938 a well-known musician remembers seeing him wander into a Chicago dancehall one night “looking beat” and without a horn.” (Under the effects of heroin all moral restraint goes and such shocking procedures ensue as the begging of money for further acquisition of the expensive drug and the practice of one musician pawning another’s instrument as well as his own.) That night he wanted to “sit in” with the band. The “alto-man” loaned him a horn and when he heard the amazing results told Charlie that since he happened to have an extra horn, and Charlie had none, it would be all right for him to keep this one. Among jazzmen this is the supreme compliment.

When he rejoined McShann the band made its first visit to New York. The foundations of Bird’s ultimate style were clearly defined though before he left for the “big” city. His phrasing was more involved, the tone a little more strident, and the pulse of each performance had a manner of swing that seemed to owe nothing to any source. His use of grace notes and certain dynamic inflections were different from anything that had been heard on the alto or any other instrument.

Musicians were beginning to talk about him and the music press took notice of his “inspired alto solos”, “wealth of pleasing ideas”, and “superb conception.” But when he arrived in New York he began experimenting with newer harmonic ideas. He fell in with a group of young musicians uptown and his influence on them has since made them important men in the new fields Bird was beginning to exploit. Musicians all over New York were asking Bird to “sit in” with their bands if only for a few solos.

Although his style was evolving into something entirely personal he did not acquire his really fabulous reputation until a couple of years later. He worked on a variety of jobs, even spending nine months working for Noble Sissle, whose band has always been further removed from jazz, and closer to the Broadway commercial concept of music than any other Negro orchestra.

“Sissle hated me”, Charlie once said. “I only had one featured number in the books and I doubled on clarinet for that job.”

Clarinet is by no means Charlie’s only “double;” from time to time he has been heard experimenting with practically every brass and woodwind instrument.

Early in 1942, under pressure from certain musicians in his band, Earl Hines tried to hire Charlie. But Hines felt badly about taking Bird away from a fellow pianist – maestro, Jay McShann. Calling McShann long distance to give him fair warning that he had musical designs on Parker, he was greeted, to his amazement, with McShann’s gleeful answer, “The sooner you take him the better. He just passed out in front of the microphone right in the middle of his solo!”

It was not until early 1943 when Bird was out of work that he finally joined Hines. Earl had to buy him a saxophone. It was in Hines’ band that Bird’s influence became felt at its strongest. The band, under Charlie’s guidance became a nursery of new ideas. It will always be one of the greatest regrets of jazz historians that this band of 1942 through 1944 never made any records, owing to the first recording ban which went into effect August 1, 1942. It was a decisive phase in the development of the new music.

When he left Earl, Charlie worked briefly with many bands and groups of musicians until he formed his own quintet featuring an eighteen year old trumpet player named Miles Davis, and pianist Bud Powell, drummer Max Roach, and bassist Curley Russell, all of whom subsequently became leaders in jazz thinking on their respective instruments admittedly as a result of Charlie Parker’s inspiration and influence. These men and a handful of others are not imitators; they are musicians of great creative imagination who went deeply into the fields that Bird had opened for them. Since the formation of that group Bird has preferred to work only in the more flexible, purer medium of the small jazz unit.

Then Charlie, Miles and a few others went to California where, they had been misinformed, were many admirers of the new jazz, Bird’s reputation having by now achieved nationwide popularity among musicians and informed listeners.

Things reached a climax one night after a recording session at which Bird had showed alarming signs of unbalance. The record he made that night, after a few strengthening shots of brandy, was ultimately released. His solo started a couple of bars late and continued incoherently; it sounds like a shadow of the real Parker. Later that night he broke down completely losing all control, he flung his horn through a closed window in his hotel room and ran crazily into the lobby causing a small riot. He remembered nothing about the next few days. Through the intercession of his friends he was sent to Camarillo State Hospital where he remained for seven months. Here, after a while, he was given physical work to do and his mind and body were built up to a point they had never reached since childhood. When he was well enough to leave the hospital, Charlie’s first thought was to get back to New York where rumor had it that the Bird was dead.

“As I left the coast they had a band at a local club,” Charlie said, “with somebody playing a bass sax and a drummer playing on the temple-blocks and ‘ching-ching’ cymbals – one of those real New Orleans style bands, that ancient jazz – and the people liked it! That was the kind of thing that had helped to drive me crazy – you know – it was always cruel for musicians, just the way it is today. They say that when Beethoven was on his deathbed, he shook his fist at the world; “they just didn’t understand.”

The musicians out on the coast gave a concert in his honor and the proceeds went toward buying him a new horn, new clothes and a plane ticket to New York along with a few hundred dollars in his pocket. When he arrived at Fifty-Second Street that tense, anxious evening, the crowd of musicians silently, respectfully greeted him and he was led into one of the clubs.

That entire street from which a great mélange of sound usually poured forth was conspicuously silent those minutes. The musicians and patrons of all the nightclubs were standing outside listening intently for the first sounds that would come forth from the Bird’s instrument. That night Charlie Parker reconquered Fifty-Second Street which was then the heart of the jazz world. Every session he appeared at for the next few weeks was ballyhooed days in advance among the modern-thinking musicians and attendance was compulsory for those who wished to continue in his sphere of influence. He was still the most brilliant musical thinker in jazz if not yet, at that time, in full possession of his technique, tone and taste. These were regained a thousandfold shortly after when Bird once more became fully accustomed to his instrument.

Now the reader probably wants to know just what his contributions were and why he is considered so great a soloist. Every capable jazz musician and most informed listeners are familiar in practice, if not in theory, with the lengthened melodic line, the broadened harmonic base, the improvised cadenzas free of measured stricture, and the accompanying balanced less regularly syncopated rhythm. These additions by Bird were vital; they helped sweep away the mold that was threatening to bury jazz. Musicians, fans and critics discovered how tightly the long melodic line, the fresh colors, and the brightly altered chords were attached to Bird’s own playing.

Today very few jazz instrumentalists born since the first World War play without a decisive Parker influence, and his influence on the older more conservative element in jazz, regardless of their opposition to change because of the false sense of security found in old patterns, has also been phenomenal. Even outside of the sphere of jazz, in the popular commercial bands, both large and small, one comes across phrases and harmonic patterns that were originated by, or at least reminiscent of Bird.

Charlie Parker brought the art of jazz improvisation to a new peak of maturity. A full appreciation of his creative ability can only be gained by lengthy study of his work both in person and on records. His mind and fingers work with incredible speed. He can imply four chord changes in a melodic pattern where another musician would have trouble inserting two. But speed is not an essential component of his style. One of the most vital qualities of Bird’s improvisation is his variety of construction. The beautiful sweeping phrases, the odd, unexpected yet charming, intervals between the notes in the melodic line, the quick passing notes which do not belong in the chord, the oblique devious approach to the harmonic pattern of the tune, the sharply contrasted staccato and legato notes, and always that bitter, caustic yet beautiful tone – these all identify Bird and the school of music he unconsciously but definitely formed.

This new way of thinking shaped musicians, pushed crude entertainment aside for imaginative ideas, and at least suggested the disciplined creative potential of a young music. Tutored by men like Charlie Parker, whose talent has long leaked beyond its narrow environment, jazz has begun to show the effects of intelligent schooling. Today one must sit and listen and study what one hears, and as a result the emotions are even more deeply affected. For it is no more a one-two body blow with which one is hit, but long rapid-fire lines, which require as complicated a response in return, and for that, one must be grateful to the Bird, thankful for the opportunity to hear his music, in all its present variations and all the new horizons he opened for jazz, and, above all, to better understand a young, struggling and much abused art.

Great story Al; I loved reading it. I’ve always been fascinated with what dealers/individuals/stores offer for collections. What was your ballpark offer if you don’t mind me asking?

Wonderful story, thank you! So much of it rang true with me

I know I speak for many – THIS IS A VERY GOOD READ. Good job Al – great Story.

Fantastic Al, and much needed during this strange time. Irving Kalus’ professor must have been happy to have such a terrific writer in his class.

Like you say, browsing through the collection of a deceased person, is like continuing the discussion and exchanges, as if he was still there.

A very moving story.

Thanks, all. Mark, perhaps one day I will share the numbers, but not yet. In retrospect, and at the time, I got a great collection, it was a bargain financially and Irving’s family was extremely pleased and grateful. I still have a good portion of the collection and I really treasure the entire experience. It was a blessing for me, not just to get the records, but to pay this tribute, particularly posting Irving’s Bird essay. As I say in the piece, it was in honor not just of Irving, but of my dad as well.

Great collecting story and wonderful piece by Irving K. Thanks for sharing (again).

It’s a beautiful piece Al no question.

Outstanding story. Thank you so much for sharing this!!

Thanks for printing that wonderful article about Irving Kalus’jazz record collection. It really hit home for me because Irv was my uncle. His wife Fran was my Dad’s sister. Karen and Gary are my first cousins. I remember when I was a kid that Uncle Irv turn me on to jazz, but my interest in jazz went a little further back than his. My favorite era is the 1920s jazz. My only exposure to modern jazz was Lew Anderson’s jazz band. That’s because I knew Lew. Uncle Irv also introduced me to Allan Sherman OH, another love of his. Thanks for a well-written article about my favorite uncle.

Pingback: Jazz Vinyl Collection For Sale | jazzcollector.com