Guest Column: Ornithology, By Irving Kalus

As promised, here is the paper written by Irving Kalus on Charlie Parker, dated December 22, 1949. I have to really admire that Irving caught on to bebop so quickly and ardently, and he recognized the genius and contribution of Bird. You can see that this paper is written with tremendous passion and feeling and probably some hyperbole that can be easily excused by the exuberance of youth. As Irving’s son Gary told me, Irving was a fan of Benny Goodman . . . well, read it and see. I’ve reprinted the entire paper below and I’m also attaching it as a downloadable PDF (Ornithology). It’s remarkably similar to the article I wrote in 1975, when I was 22 and had the benefit of 20 years of history after Bird had died. You can find my article here: An Old Jazz Collector Tribute to Charlie Parker. Irving was neither a writer nor jazz critic by trade, but he certainly had a gift for both and, from now on, perhaps forever, whenever anyone does a Google search linking on Irving Kalus, the names Charlie Parker and Irving Kalus will be inextricably tied together. It’s a nice thought and a pretty apt tribute, wouldn’t you say?

As promised, here is the paper written by Irving Kalus on Charlie Parker, dated December 22, 1949. I have to really admire that Irving caught on to bebop so quickly and ardently, and he recognized the genius and contribution of Bird. You can see that this paper is written with tremendous passion and feeling and probably some hyperbole that can be easily excused by the exuberance of youth. As Irving’s son Gary told me, Irving was a fan of Benny Goodman . . . well, read it and see. I’ve reprinted the entire paper below and I’m also attaching it as a downloadable PDF (Ornithology). It’s remarkably similar to the article I wrote in 1975, when I was 22 and had the benefit of 20 years of history after Bird had died. You can find my article here: An Old Jazz Collector Tribute to Charlie Parker. Irving was neither a writer nor jazz critic by trade, but he certainly had a gift for both and, from now on, perhaps forever, whenever anyone does a Google search linking on Irving Kalus, the names Charlie Parker and Irving Kalus will be inextricably tied together. It’s a nice thought and a pretty apt tribute, wouldn’t you say?

Ornithology

by Irving Kalus

Paper submitted for Adv. Comp. class, Department of English, NYU

December 22, 1949

Fifty-Second Street was crowded that night late in April 1947. The crowd was composed, as it usually is on this particular New York street off Seventh Avenue, mostly of musicians. But the usual calm, stoical attitude of these men had changed that evening to one of eager excitement and almost nervous apprehension. A feeling of electrical tension was in the air and over the buzzing musicians and music-lovers and the anxious queries of passersby one could hear, “The Bird’s back in town.” From one club to another, from one bar to another the words had been whispered in sepulchral tones usually reserved for religious leaders and revolutionaries.

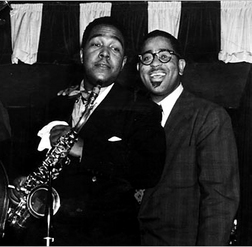

What manner of being could cause this kind of excitement? Who is the “Bird”? The “Bird” is a musician- a jazz musician. He plays the alto saxophone. His real name is Charlie Parker but the nickname “Bird”, whose origin even its owner can’t determine, is the one all musicians speaking of or to him, use. The following statements made by people in the jazz world are typical of the attitude of respect and even idolatry in which Charlie Parker is held:

“Bird is the greatest instrumentalist I’ve ever heard. He can express anything he can think of on his horn. And if he thinks of more than he plays then he’s even greater than we believe he is,” said Charlie Ventura, a fellow saxophonist.

“Bird is in a class completely by himself. The wonderful fluid continuity of his playing, the delicacy of his phrasing – his ideas make music,” said Freddy Wilson.

“I think Charlie has the greatest sense of time – the greatest feel of time. And his wealth of ideas. So different and so melodic. He thinks so much faster than anyone else – his music tells a story,” said Duke Ellington.

One of his disciples, a young, highly-regarded trumpet player said this of Bird:

“I studied at the Washington Conservatory and then at Julliard but I learned more from playing and talking to Charlie Parker.”

But another young musician, one who was performing in one of the nightclubs on Fifty-Second Street that anxious evening summed up the underlying feeling of the entire jazz world when he said:

“Bird has conquered the harshness of jazz and expressed pure beauty – his influence on our music and our lives is too great for me to define.”

All this enthusiasm elicited for a jazz musician may seem exaggerated or even ludicrous to those who have never really understood America’s greatest contribution to the Arts. We have come to regard this young struggling music form, through the commercially distorted views we get of it, as childish, faddish, unimportant and even offensive music. The word “jazz” has come to be regarded as synonymous with vulgarity and commercialism, and I cannot deny that this opinion is at least partially justified in lieu of the fact that what is heard of the music and referred to as jazz is usually at best no more than a gross caricature of a pure, moving, soulful and more recently an intelligently thoughtful art. Those who in their attempts “refine” the music and make it more palatable for public consumption have not only profited by squelching the young art but added to the popular misconceptions already formed. To condemn the pimps and prostitutors of jazz such as the Paul Whitemans, George Gershwins and lesser lights like the Dorsey brothers, Harry James, and those half-sincere musicians like Benny Goodman and his ilk is not directly my purpose in writing this paper. My purpose is to bring to light a key figure in jazz, one who has been responsible for a revolution in the music – a revolution which began in the early nineteen-forties and whose scope and dimensions none of us were astute enough to predict at the time.

It has been the fortune of jazz to elude any and all attempts to tie it down, even to words. For better or for worse, the very name of this music has resisted any really satisfactory explanation. Often, when the whole can’t be defined, it is possible to make some sense out of it by summing up its parts. But when a part grows so big that it almost eclipses the whole, as Charlie Parker’s music has spurted beyond the confines of jazz, simple definition becomes utterly impossible and complex description must take its place. But complex description cannot and will not be understood by the lay public so the best that can be done is to give a brief biography of the man who raised jazz to a really thoughtful level, who gave it freshness, form and profundity, and to explain as adequately and yet as simply as possible how this rather awesome feat was accomplished.

The story begins on August 29, 1920 when Bird was born in Kansas City. He went through elementary school, spent three years in high school and would up a freshman. He played baritone horn in the school band and started seriously on the alto at the age of fifteen, when his mother bought him one.

Charlie was introduced to night life at its most lurid when he was still an immature lad of about fifteen. Basically he was not anti-social or morally bankrupt, but his true character was warped by contact with vicious elements in the Kansas City underworld, and his entire life and professional career have been colored both by these contacts and his background of insecurity and racial discrimination. The Bird is a Negro.

Charlie spent many years fighting an addiction which was wrecking his life. His dissipation began as early as 1932, taking a more serious turn in 1935 when an actor friend told him about a new “kick”. It was then that the addiction to marijuana, which, regardless of all misinformed statements to the contrary, is a fairly mild dope, gave way to the really nerve shattering and sometimes completely collapsing drug- heroin. One morning very soon afterwards he woke up sick and not knowing why. The panic, the eleven year panic was on. Eleven years were ripped from his life. As Bird once confessed in an informal interview:

“I didn’t know what hit me –it was so sudden. I was a victim of circumstances. High school kids don’t know any better. That way you can miss the most important years of your life, the years of possible creation. I don’t know how I made it through those years. I became bitter, hard, cold. I was always on a panic, couldn’t buy clothes or a good place to live. Finally out on the coast I didn’t have any place to stay until somebody put me up in a converted garage. The mental strain was getting worse all the time. What made it worst of all was that nobody understood our kind of music out on the coast. They hated it. I can’t begin to tell you how I yearned for New York.”

Shortly afterwards Charlie went into the physical and mental decline that has become legendary in jazz history. But more on that later. First we will follow his career as a musician up to that almost fatal point.

Charlie first went to work for a bandleader named Jay McShann who came to Kansas City in 1937. He left and rejoined this band a few times and gained some of his other early experience with local bands. As early as 1938 a well-known musician remembers seeing him wander into a Chicago dancehall one night “looking beat” and without a horn.” (Under the effects of heroin all moral restraint goes and such shocking procedures ensue as the begging of money for further acquisition of the expensive drug and the practice of one musician pawning another’s instrument as well as his own.) That night he wanted to “sit in” with the band. The “alto-man” loaned him a horn and when he heard the amazing results told Charlie that since he happened to have an extra horn, and Charlie had none, it would be all right for him to keep this one. Among jazzmen this is the supreme compliment.

When he rejoined McShann the band made its first visit to New York. The foundations of Bird’s ultimate style were clearly defined though before he left for the “big” city. His phrasing was more involved, the tone a little more strident, and the pulse of each performance had a manner of swing that seemed to owe nothing to any source. His use of grace notes and certain dynamic inflections were different from anything that had been heard on the alto or any other instrument. Musicians were beginning to talk about him and the music press took notice of his “inspired alto solos”, “wealth of pleasing ideas”, and “superb conception.” But when he arrived in New York he began experimenting with newer harmonic ideas. He fell in with a group of young musicians uptown and his influence on them has since made them important men in the new fields Bird was beginning to exploit. Musicians all over New York were asking Bird to “sit in” with their bands if only for a few solos.

Although his style was evolving into something entirely personal he did not acquire his really fabulous reputation until a couple of years later. He worked on a variety of jobs, even spending nine months working for Noble Sissle, whose band has always been further removed from jazz, and closer to the Broadway commercial concept of music than any other Negro orchestra.

“Sissle hated me”, Charlie once said. “I only had one featured number in the books and I doubled on clarinet for that job.”

Clarinet is by no means Charlie’s only “double;” from time to time he has been heard experimenting with practically every brass and woodwind instrument.

Early in 1942, under pressure from certain musicians in his band, Earl Hines tried to hire Charlie. But Hines felt badly about taking Bird away from a fellow pianist – maestro, Jay McShann. Calling McShann long distance to give him fair warning that he had musical designs on Parker, he was greeted, to his amazement, with McShann’s gleeful answer, “The sooner you take him the better. He just passed out in front of the microphone right in the middle of his solo!”

It was not until early 1943 when Bird was out of work that he finally joined Hines. Earl had to buy him a saxophone. It was in Hines’ band that Bird’s influence became felt at its strongest. The band, under Charlie’s guidance became a nursery of new ideas. It will always be one of the greatest regrets of jazz historians that this band of 1942 through 1944 never made any records, owing to the first recording ban which went into effect August 1, 1942. It was a decisive phase in the development of the new music.

When he left Earl, Charlie worked briefly with many bands and groups of musicians until he formed his own quintet featuring an eighteen year old trumpet player named Miles Davis, and pianist Bud Powell, drummer Max Roach, and bassist Curley Russell, all of whom subsequently became leaders in jazz thinking on their respective instruments admittedly as a result of Charlie Parker’s inspiration and influence. These men and a handful of others are not imitators; they are musicians of great creative imagination who went deeply into the fields that Bird had opened for them. Since the formation of that group Bird has preferred to work only in the more flexible, purer medium of the small jazz unit.

Then Charlie, Miles and a few others went to California where, they had been misinformed, were many admirers of the new jazz, Bird’s reputation having by now achieved nationwide popularity among musicians and informed listeners.

Things reached a climax one night after a recording session at which Bird had showed alarming signs of unbalance. The record he made that night, after a few strengthening shots of brandy, was ultimately released. His solo started a couple of bars late and continued incoherently; it sounds like a shadow of the real Parker. Later that night he broke down completely losing all control, he flung his horn through a closed window in his hotel room and ran crazily into the lobby causing a small riot. He remembered nothing about the next few days. Through the intercession of his friends he was sent to Camarillo State Hospital where he remained for seven months. Here, after a while, he was given physical work to do and his mind and body were built up to a point they had never reached since childhood. When he was well enough to leave the hospital, Charlie’s first thought was to get back to New York where rumor had it that the Bird was dead.

“As I left the coast they had a band at a local club,” Charlie said, “with somebody playing a bass sax and a drummer playing on the temple-blocks and ‘ching-ching’ cymbals – one of those real New Orleans style bands, that ancient jazz – and the people liked it! That was the kind of thing that had helped to drive me crazy – you know – it was always cruel for musicians, just the way it is today. They say that when Beethoven was on his deathbed, he shook his fist at the world; they just didn’t understand.”

The musicians out on the coast gave a concert in his honor and the proceeds went toward buying him a new horn, new clothes and a plane ticket to New York along with a few hundred dollars in his pocket. When he arrived at Fifty-Second Street that tense, anxious evening, the crowd of musicians silently, respectfully greeted him and he was led into one of the clubs. That entire street from which a great mélange of sound usually poured forth was conspicuously silent those minutes. The musicians and patrons of all the nightclubs were standing outside listening intently for the first sounds that would come forth from the Bird’s instrument. That night Charlie Parker reconquered Fifty-Second Street which was then the heart of the jazz world. Every session he appeared at for the next few weeks was ballyhooed days in advance among the modern-thinking musicians and attendance was compulsory for those who wished to continue in his sphere of influence. He was still the most brilliant musical thinker in jazz if not yet, at that time, in full possession of his technique, tone and taste. These were regained a thousandfold shortly after when Bird once more became fully accustomed to his instrument.

Now the reader probably wants to know just what his contributions were and why he is considered so great a soloist. Every capable jazz musician and most informed listeners are familiar in practice, if not in theory, with the lengthened melodic line, the broadened harmonic base, the improvised cadenzas free of measured stricture, and the accompanying balanced less regularly syncopated rhythm. These additions by Bird were vital; they helped sweep away the mold that was threatening to bury jazz. Musicians, fans and critics discovered how tightly the long melodic line, the fresh colors, and the brightly altered chords were attached to Bird’s own playing. Today very few jazz instrumentalists born since the first World War play without a decisive Parker influence, and his influence on the older more conservative element in jazz, regardless of their opposition to change because of the false sense of security found in old patterns, has also been phenomenal. Even outside of the sphere of jazz, in the popular commercial bands, both large and small, one comes across phrases and harmonic patterns that were originated by, or at least reminiscent of Bird.

Charlie Parker brought the art of jazz improvisation to a new peak of maturity. A full appreciation of his creative ability can only be gained by lengthy study of his work both in person and on records. His mind and fingers work with incredible speed. He can imply four chord changes in a melodic pattern where another musician would have trouble inserting two. But speed is not an essential component of his style. One of the most vital qualities of Bird’s improvisation is his variety of construction. The beautiful sweeping phrases, the odd, unexpected yet charming, intervals between the notes in the melodic line, the quick passing notes which do not belong in the chord, the oblique devious approach to the harmonic pattern of the tune, the sharply contrasted staccato and legato notes, and always that bitter, caustic yet beautiful tone – these all identify Bird and the school of music he unconsciously but definitely formed. This new way of thinking shaped musicians, pushed crude entertainment aside for imaginative ideas, and at least suggested the disciplined creative potential of a young music.

Tutored by men like Charlie Parker, whose talent has long leaked beyond its narrow environment, jazz has begun to show the effects of intelligent schooling. Today one must sit and listen and study what one hears, and as a result the emotions are even more deeply affected. For it is no more a one-two body blow with which one is hit, but long rapid-fire lines, which require as complicated a response in return, and for that, one must be grateful to the Bird, thankful for the opportunity to hear his music, in all its present variations and all the new horizons he opened for jazz, and, above all, to better understand a young, struggling and much abused art.

Wow

Great, great story. Especially the quotes by Parker himself are interesting. And while I was reading, it struck me: this was written in 1949, which means that Parker was still alive, as we all know he died 6 years later. You get so used to reading material that was written many, many years after Parker’s death that you hardly expect to read something written when he was still on this planet. Hats off to Irving!

Great piece of writing! I wonder what the instructor thought, and what he received for a grade!

This is a wonderfully well-written piece. I don’t know if Nat Hentoff or Orin Keepnews could have written it any better. Wow! Hat’s off to Irving Kalus.

This is the best description of Bird I’ve ever read. More feeling here than in the whole Ross Russell book.

And that smile-oh my god! All the balls and hope of the old world Jewish lefties like Abel Meeropol—composer of “Strange Fruit” and adopter of the Rosenberg orphans.

And your own grandpa too, Lit. These were good people-

While the piece on Bird is valuable for both its timing and insight, its location within the broader narrative that Al has constructed surrounding Irving’s life, his love of jazz, and his lp collecting increases its value for this reader.

There is much in this paper I would have loved to discuss with my father, but I actually never read it until after he died on December 22. My sister had kept it with her valuables. I knew he had a deep understanding of the music he loved so much and it spoke to him. He would often tell me how the “hornman” was speaking through his horn.

I was floored by his comment about Benny Goodman, who he always spoke highly of. I asked Al to count the number of Benny Goodman records in his collection and they numbered about 50, so his view in 1949 about the greater jazz world was tempered pretty soon afterward. Not so his love of Bird. An often repeated quote from my father throughout the years, whenever he saw or heard a popular musician who was making a ton of money, but whose music held little value in my father’s view, was “And Charley Parker died a pauper.” The comment was always accompanied by a look of disgust at the injustice of it all.

Great article. Something I would have loved Irv to share, but he never did. I know one of his favorite tenor sax men was Brew Moore. He recounted many of the club dates he saw Brew and the sidemen in New York in the late 40’s and early 50’s. He met him as well. Well written and as articulate as Irv was in spoken word as well.

Hey, Gary. I’m with your dad on Benny Goodman, particularly if you look at it through the prism of 1949. Bebop was the music of the times, of the next generation, of youth, and it was an innovation that had passed over many of the stars of the previous generation. There were many jazz greats who had the passion, talent and belief to make the transition to the new music, Coleman Hawkins is a favorite of your dad’s who comes to mind, while others continued to play in the style that had brought them fame and, in Goodman’s case, fortune. In 1949 it’s easy to see where fans of bebop would resent some of the musicians of the previous generation, no matter how great they may have been in their era, for not fully supporting and embracing the new music and the new generation of musicians. Louis Armstrong sung of the boppers — “They are poor little cats that have lost their way.”

Yes, but I don’t believe that my father would have ever had anything bad to say about Satchmo at any time in his life. Whenever he heard his voice or the sound of his trumpet, my father would smile and say “Ah, Louey.”

So you think paragraph 7 is Irving quoting Miles Davis? That would be interesting given the last events of his life.

Pingback: Later Pressings and Rising Prices: Merry Christmas | jazzcollector.com