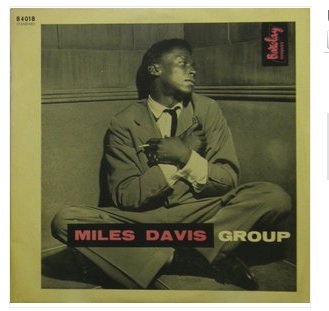

The “Infamous” Junkie Cover?

Once again we will travel to France for today’s post thanks to our friend CeeDee, who seems to be inspiring a few of our reports lately. This one concerns this record: Miles Davis Group, Barclay 84.018. This was an original 10-inch French pressing that looked to be in VG++ condition for the record and VG+ for the cover. It consists of music from the Prestige “Dig” date, featuring Sonny Rollins and Jackie McLean. In his note to me, CeeDee described this as “the infamous junkie cover.” I had to confess my ignorance. I had never seen this cover before, nor had I ever heard of the picture and the reference to a junkie cover. I asked CeeDee what he knew. Apparently, he doesn’t know much in terms of details but said he’s always heard that’s how this particular cover was usually referenced by collectors and the image has rarely been produced in any format. He suggests that some of our European readers will have what he describes as the “grim details.” So let’s put it out there and see what comes back. The record sold for $577.89, by the way. I have a feeling after this post and subsequent comments, the value may go up even higher. I will say I, for one, am newly intrigued by this record.

Once again we will travel to France for today’s post thanks to our friend CeeDee, who seems to be inspiring a few of our reports lately. This one concerns this record: Miles Davis Group, Barclay 84.018. This was an original 10-inch French pressing that looked to be in VG++ condition for the record and VG+ for the cover. It consists of music from the Prestige “Dig” date, featuring Sonny Rollins and Jackie McLean. In his note to me, CeeDee described this as “the infamous junkie cover.” I had to confess my ignorance. I had never seen this cover before, nor had I ever heard of the picture and the reference to a junkie cover. I asked CeeDee what he knew. Apparently, he doesn’t know much in terms of details but said he’s always heard that’s how this particular cover was usually referenced by collectors and the image has rarely been produced in any format. He suggests that some of our European readers will have what he describes as the “grim details.” So let’s put it out there and see what comes back. The record sold for $577.89, by the way. I have a feeling after this post and subsequent comments, the value may go up even higher. I will say I, for one, am newly intrigued by this record.“What do you mean, a habit?” I said.

Matinee told me “Your nose is running, you got chills, you weak. You got a motherfucking habit nigger.” Then he bought me some heroin in Queens. I snorted the stuff Matinee copped for me and I felt just fine. My chills went away, my nose stopped running and I didn’t feel weak no more.

I continued my snorting by when I saw Matinee again, he said, “Miles, don’t waste that little money on getting some to snort, because you still gonna be sick. Go on and shoot it, then you’ll feel much better.” That was the beginning of a four-year horror show.

–Miles Davis in “Miles: the autobiography“, page 132

For some time he’d been snorting diluted heroin and cocaine, but with only short-term highs, and if he missed a day, he’d be hit with aches, fever, and chills; a gradual weakness took over, and his nose was constantly streaming. A friend told him that he had a habit and that inhaling was an expensive waste of the drug, so he began injecting it. First, he got high alone, but he hated the idea of becoming a junkie who roamed the streets with the drug as his only friend. He moved instead into one of those small circles of users who “roomed” with each other — regularly getting high together someplace in the city, borrowing and stealing from each other, bound together in a strange comitatus, a fellowship of the needle in the name of bebop.

Miles’ behavior changed quickly. He became withdrawn, distant, passive, asexual. The transformation was so rapid and profound that at first Irene suspected him of being with other women, then discovered it was drugs: Miles began coming home later and later in the evening. “I accused him of drugs, because I’d found a spot of blood on his shirt. He grabbed the shirt out of my hand and said nothing. I got him an appointment with a psychiatrist, and he went once. But he never went again because he said the psychiatrist was crazy.”

Miles’ daily commutes to Manhattan were becoming shopping trips for narcotics. “My mother was a country girl at the time,” their son Gregory said, “and she could see the deterioration of his character. I remember my mother trying to hide his shoes from him so that he wouldn’t be able to go out to cop.” And when Miles was at home, his depression deepened:

“Irene and I didn’t have any kind of family life anyway. We didn’t have a whole lot of money to do things with, with the two kids and ourselves to feed and all. We didn’t go anywhere. Sometimes I used to stare in space for two hours just thinking about music….I basically left Irene sitting at home with the kids because I didn’t want to be there. One of the reasons I didn’t want to be there was that I felt so bad that I couldn’t hardly face my family. Irene had such confidence and faith in me….But Irene knew. It was all there in her eyes.”

“One Thanksgiving we didn’t have the money for a turkey,” Irene said, “so we bought as big a chicken as we could, and Miles told the children, ‘See the turkey?’ When Easter Sunday came, I asked Miles to pick up some dye for Easter eggs. But when I brought the children home from church, Miles had just drawn on the eggs with a pencil.”

Smack, junk, skag, horse, shit, H. It had as many names as an ancient god, which for some it seemed to be. Heroin was the ultimate high. It could remove the constant knot from your stomach, or make you think you’d always had one there before you’d used it. It was not so much that it could bring you euphoria and erase the day-to-day concerns of family and job, but it could take away the surprises and lower emotions. St. Louis hipster Ollie Matheus recalled Charlie Parker’s praise for his drug of choice: “Bird says it’s like a loan. You consolidate all your loans into one payment; that’s a junkie. All of life’s problems are one problem.” Like driving in a fast car — something Miles would soon grow to love — heroin narrowed the emotional and visual fields to only the moment. It gave a crystalline vision of the music, slowing the music down as well, stopping and holding up to the light those beautiful bop melodies that otherwise could fly by so fast that they left nothing but vapor trails. Before club gigs or recording dates, the musicians could be seen fanning out across the city looking to score — up to the roof of a place in Hell’s Kitchen, into a Spanish restaurant on Eighth Avenue, uptown to a certain corner. A musician prepares.

With Miles, a certain remoteness also set in; his attention span shortened, and his distance from others increased. The drug itself became the object of his affection. In an insecure and capricious world, it was something he could count on to work, and work again and again, forming a ritual of return that in itself stabilized and gave solace. Beyond that, it was the key to the door of the restricted club of those who know. Pianist Walter Davis described the exclusivity of drugs this way:

“I just know that when you got high at that time, you were further into the clique….It was in to be doing that. [When somebody was playing well] conversation went like this: you would always hear somebody say, “Who the hell is that?” Guy say, “Well, that’s such and so,” and the next question would be, “Does he get high?” You say, “Yeah, he gets high as a motherfucker.”

Heroin was emblematic for some musicians, a sign of alienation from a certain kind of society. It was, after all, a crime to use it. For Miles, it signified that he was not a square — or a dentist. Yet like all other junkies, life for him was now built around drugs. He had to find them, had to cop, score, deal. He had to protect himself against rip-offs of all sorts, everything from impure product to bad counts. He had to watch his transactions like any middle-class man of commerce, and make sure that he timed every part of the process correctly so that he wasn’t nodding during the set, wasted before the gig, or arrested. Heroin took time, labor, and planning, and when he traveled anywhere, the problems were compounded: where to cop, and where to go if he got sick? He would ultimately declare that heroin was boring — the waiting, living in the present, all those rituals of use — but for now it was the cost of feeling safe for the moment.

Heroin is an illusory drug, its continuous use a source of physical pain, disappointment, and heartbreak, each hit less satisfying than the previous one, until a nostalgia for the first time drives the urge. Miles soon hit bottom, and went so low that he saw something in himself that he could never forget. He had crossed the line, and even when he was off drugs, the experience haunted him. He constructed a vision of his experience that changed him from a “nice, quiet, honest, caring person into someone who was the complete opposite.” It was simplistic but in a sense true. He was pawning his horn (renting Art Farmer’s trumpet when he could), begging others for money, lying, cheating, and stealing from those closest to him.

Irene, desperate, turned to anyone whom she thought might help her. “Once I went to Birdland to talk to Charlie Parker about Miles using drugs, and he was sympathetic, and seemed surprised that Miles was using. He said he’d give him a good talking to.” When nothing else worked, she called Miles’ father to tell him that she had no way of coping with drugs. Though he never mentioned how his father reacted, his sister said, “When Miles put that needle into himself, he put it into the whole family.” Miles did recall the disgrace of being discovered in the gutter on Broadway by Clark Terry, of being fed and put to bed in Terry’s room, only then to steal his clothes and radio and pawn his trumpet. When Pauline, Terry’s wife, called Miles’ father to tell him what was happening to his son, his father turned on Clark, blaming him and other musicians in New York.

Babs Gonzales, consummate hipster and bebop singer (and, some would say, not always reliable raconteur), tells of an evening in Chicago during this period where Miles, his brother, Vernon, and another man were setting up a small-time drug-dealing scam in order to trick a hometown man into giving them $300 for drugs, which they would use to pay the hotel bill. But the mark spotted what they were up to, and Miles and Vernon were put out of the hotel.

Reflecting back on his worst days on heroin, Miles would later say that he had become a pimp in order to survive. “Under heroin, you could pimp yourself, your mother, anyone,” he told a girlfriend later. If he was a “pimp” it was not in the sense that white people use the term, as a noun, as someone in The Life, a man who runs women on the streets for profit. He was a pimp only in that he took gifts from women who lived by selling sex, as well as from those who didn’t. “Player” might be the better term, a ladies’ man, one who manipulates women to support his habit or his lifestyle. But Miles could also play at being the mackman, using pimp talk to flirt with women, as well as talking with the kind of verbal aggressiveness that kept men at bay. The conceit or fantasy of living off women was not uncommon among some men, something you could find in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and in the ambivalent claims made by Charles Mingus about himself in his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog (though those who knew Mingus also denied that he ever pimped women). As an upper-middle-class young man, the role of the pimp fascinated Miles — the walk, the talk, the dress, the attitude of the wily trickster in control of every situation, the black businessman operating outside the reach of white commerce. Yet years later, when he was cast in the role of a pimp on the television show Miami Vice, he complained about it, to his brother’s amusement.

He boasted in his autobiography that between 1951 and 1952, “I had a whole stable of bitches out on the street for me.” Yet he quickly added, “It wasn’t like people thought it was; these women wanted someone to be with and they liked being with me. I took them to dinner and shit like that….I just treated the prostitutes like they were anybody else. I respected them and they would give me money to get off in return. The women thought I was handsome and for the first time in my life, I began to think that I was, too. We were more like a family than anything.”

He explained that the women wouldn’t give me their money. They just give me money to take them out. They made a lot of money…screwin’. They didn’t give all their money to me, they just said, “Miles, take me out. I don’t like people I don’t like, I like you, take me out…” That’s like a family they like to be in. I know, I can understand that. “I was getting by with the help of women; every time I really needed something during this period I had to go to women to get it. If it hadn’t been for the women who supported me, I don’t know how I would have made it without stealing every day like a lot of junkies were doing. But even with their support, I did some things I was sorry for later.”

Miles never glamorized the drug experience or turned it into a horror story. And if, like other junkies, he developed a tale of decline and self-destruction, it was at least a minimalist narrative as sparse as his speech and his playing. For much of his time under heroin, he was not fully addicted, though he suffered flulike symptoms, malaise, headaches, and weakness. It was a matter of pride to him that he not be seen nodding. Other symptoms of drug use — like mood swings, forgetfulness, and unhappiness — he hoped would be treated as merely part of his character.

Thinking he might find work (and drugs) more easily if he were living in Manhattan again, Miles moved his family into the Hotel America on 48th Street, where Clark Terry, singer Betty Carter, and a number of other musicians stayed. “Betty worshipped Miles,” Irene said, so Miles talked Betty into letting the children and Irene move in with her and share the rent. Irene had recently found a job in the Admissions Department at the Brooklyn Jewish Hospital. Since Betty sang in clubs at night, she could take care of the children during the day.

In the last part of 1949, Miles played at a few high-profile events: a Town Hall concert with Erroll Garner, Lennie Tristano, Charlie Parker, and Harry Belafonte; two weeks with the Bud Powell group at the Orchid Club (the old Onyx); a short stay at the Hi-Note Club in Chicago; and a Christmas Day “Stars of Modern Jazz” concert at Carnegie Hall. But work was otherwise hard to come by, and he whiled away some of the days in rehearsal bands organized by Gene Roland and Tadd Dameron. In January 1950, he went to Chicago and Detroit to do a few guest spots with tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray, who had come in from California. While he was in Chicago, Miles’ father continued to send him money, but now through his brother, Vernon, to make sure it wasn’t spent on drugs. But before the month was over, Miles asked Vernon to let him have $100 so that he could loan it to Wardell, who needed it to get home. Vernon was suspicious about how the money might be used and never got his money back.

Miles returned to New York in March to finish the last of the Birth of the Cool sessions and in May he recorded with a small group accompanying Sarah Vaughan on four singles she made for Columbia Records. On ballads like “It Might as Well Be Spring” he wove obbligatos softly through her lines, complementing them perfectly. He was filling the same role Freddie Webster had played on her records four years before.

Changing musical tastes, police closings of clubs, and real estate speculation in midtown Manhattan began to drive rents out of the reach of club owners, and jazz lost out to strip clubs and bars without entertainment. But the area still had appeal for musicians and audiences. It was near restaurants like Lindy’s and Jack Dempsey’s, the Arcadia and Roseland Ballrooms, the CBS recording studios, and the Nola Studios, the largest rehearsal hall in New York City. And the Roost had enough success with bebop to encourage a few new clubs to spring up nearby — Bop City, and most notably, Birdland, which opened just before Christmas in 1949.

Birdland was located below street level at 1678 Broadway just off the corner of 52nd Street, where the lettering on an awning proclaimed, “The Jazz Corner of the World.” It was a big room that could hold 500 people, with a long bar, tables, booths, and a fenced-in “bullpen” — a drinkless area where teenagers sometimes were allowed in to watch. Birdland was the closest thing to a pure jazz club at the time, a place where new bands were born, new alliances formed, and modern musicians felt at home. But it was also a site of drug dealing, hustling of various sorts, and violence. Irving Levy and Morris Primack were the owners of Birdland, though it was operated by Oscar Goodstein, who took tickets and tended bar. Levy himself was stabbed to death in front of the club (in what the papers called “the bebop killing”) and was replaced by his brother Morris, who succeeded so well that he went on to open other clubs like the Down Beat, the Round Table, and the Embers. Morris would later own Roulette Records and the Strawberries chain of record stores, and through his mob ties and criminal activities, was finally convicted in 1988 of extortion and sentenced to federal prison. The Birdland management were starkers, tough guys. Charles Mingus recalled seeing Irving Levy kicking musicians downstairs — “‘Get down the stairs, nigger,’ you know?” For musicians who worked there five sets a night, six nights a week, it was hard and sometimes even dangerous work.

Miles became a regular at Birdland, bringing a band in for a few days, sitting in on the Monday night jam sessions, or just sitting at the bar. It was a scene he found strangely comfortable: the gruff, hipper-than-thou Symphony Sid who emceed the late sets for radio; the miniature doorman Pee Wee Marquette (who could blow cigar smoke in your face or insult you in his stage introductions if your tips weren’t right); and the thuggish Mo Levy. For much of the first half of 1950, Birdland was virtually Davis’ only source of work, but it was one that would give him notoriety. A certain kind of celebrity was drawn to Birdland, where Miles was the most interesting and stylish fixture. The Journal-American columnist Dorothy Kilgallen was a regular, and often seen chatting with Miles. Ava Gardner always dropped in when she was in town and, in later years, came in one night with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Gardner, who had worked with Juliette Greco in The Sun Also Rises, went back to the dressing room between sets to see Miles. Not every celebrity left happy: British novelist Kingsley Amis came by one evening in 1958, and later wrote in his Memoirs that he had tried to forget what he heard, but “the sound of Miles Davis’ trumpet, introverted, gloomy, sour in both senses, refuses to go away. I had heard the future, and it sounded horrible.”

As quickly as Davis’ fame spread in New York, his life away from the bandstand began to unravel. He had fallen behind in his rent at the hotel, the loan company was trying to repossess his car, and Irene learned that she was pregnant again — with a child that Miles doubted was his own. In July, he put his family in the car and drove back to East St. Louis, only to be humiliated by having his car towed from in front of his father’s house almost as soon as they arrived. Irene, Miles, and the children then moved in with Miles’ mother in Chicago, where she had bought property and was living part of the time, and where his sister, Dorothy, was teaching and Vernon was studying music.

In Chicago, Miles met Johnny Bratton, a flashy welterweight boxer from Arkansas who had made the city his home base. Bratton was a year younger than Miles, and they were similar in physique and tastes, though the fighter dressed a bit flashier, with brilliantined hair and a fondness for purple shirts. He was a classy and graceful fighter and took on some of the best boxers, like Ike Williams and Beau Jack. When Sugar Ray Robinson moved up to middleweight status in 1951, Bratton took the welterweight title and held it for a few months until the Cuban Hawk, Kid Gavilan, took it away from him. According to Irene, “Miles became friends with Johnny, and started getting really serious about boxing while we were in Chicago.”

“Miles and I went out with Johnny a few times, and he drove us around town in his new convertible. One time the cops stopped him for speeding when we were with him, but let him go when they recognized him. “It’s Honey Boy Bratton!” Miles was really impressed by that. When he got back to New York City he began to train hard.”

Bratton fought professionally for eleven years, but his career ended badly, and he wound up living in his car, then homeless, and finally in and out of mental hospitals. But it was said he was a sharp dresser even to the end.

When Irene give birth to Miles IV, their second son, Davis returned to New York to join Billy Eckstine in August, 1950, for a tour with a small group B was assembling — the All-American All-Stars — and wound up at a big concert with the George Shearing Quintet at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles on September 15. As they were on their way to the plane at the Burbank airport after that concert, drummer Art Blakey suggested they make a drug run by a house he knew. As they did, the police followed them and arrested Davis and Blakey for possession of heroin capsules. In his autobiography, Davis says that he was off heroin at the time, and that Blakey had testified against him in order for him to get himself off from drug charges. But saxophonist Hadley Caliman was in the county jail when Art and Miles were put in his cell, and he recalls it differently:

“I see this real black guy there with his hair standing straight up on his head. He had this hair straightener on his hair. And I see it’s Miles Davis….Miles was trying to wean off. Everybody who is hooked tried to wean off. They had to have a good friend, straight like Art Blakey, who could put it in his pocket and keep it. So when the police busted ’em, Miles ain’t got nothin’ but the marks [on his arms] and Art Blakey got the shit. So Art Blakey gets busted for possession. He’s like doling it out to Miles so he won’t go hog wild.”

New prisoners were given a rough initiation on their first day and tricked by inmates into believing that they might be killed by one of the crazed prisoners. Miles took the teasing badly, Caliman said: “He was very soft. He cried a little bit. He didn’t like the fact that he was incarcerated with these thugs.” Irene said that Miles always tried to talk himself out of things. He once got away with giving a cop money for a speeding ticket. He got off from a drug arrest in Harlem once by joking with the officers, telling them they held their guns too high….So in California he tried to buy his way out of it and there he got charged with bribery. He called his father, and he got him a lawyer who was a family friend, but he let it come to trial. And while he was in jail, he got over drugs for a while.

When he was released on bail, Miles stayed with Dexter Gordon, then moved into a hotel, waiting for the trial to begin. When he went to court in November, Irene told him to “dress well, wash your face, and they’ll know you didn’t do it.” It was over quickly, the jury voting ten to two in his favor, and he was released (Irene said that “a little lady on the jury told him that she knew he couldn’t do anything like that”). But only days later Down Beat editorialized on the subject of drugs in the music business, with Davis and Blakey singled out as examples. After such national attention, both men began to have even greater problems finding work.

Miles returned to East St. Louis to wait until December, when he was booked into the Hi-Note Club on the north side of the Loop in Chicago, playing opposite Billie Holiday. On the opening day of his engagement, December 22, the temperature fell to 15°F below zero, and the streets were jammed with traffic following a nearby chemical plant explosion. Miles arrived without a band but picked up a local bassist and a drummer, and Holiday agreed to share her pianist, Carl Drinkard, though she was notorious for jealously keeping her musicians to herself. After being paid each night, Miles and two of the musicians bought heroin, then went to one of their apartments or Miles’ hotel room, where they got high and worked on music for the next night in the club. According to Drinkard, Miles would “shoot up just as often as his money would allow him. You space it according to how much your money will allow you. Nobody ever really has as much as they want.” Miles’ father was still supporting him, now sending him $75 a week and paying for his phone calls, which allowed him to stay at good hotels for $28 a week and still afford heroin at a dollar a cap.

Miles was finishing his last week at the Hi-Note as 1951 began, when he received a call from Bob Weinstock, who had been calling for him around St. Louis to offer him a $750 advance to record for his new company, Prestige, whenever Miles got back to New York. Then Charlie Parker called asking him to record with him for Verve records. Metronome magazine’s readers had meanwhile voted him the top jazz trumpet player of 1950. With the drug charges behind him, things seemed to be looking up.

Weinstock was typical of the small record company owners who operated outside the mainstream. Much like Ross Russell of Dial, he had started as a jazz fan, became a record collector, then sold records by mail order, and moved on to owning his own shop in Manhattan, the Jazz Corner, selling mostly dixieland and swing. From there, he began to make records, mostly of dixieland revivalists. One of his customers, Kenny Clarke, first took him to hear bebop at the Royal Roost. Then Ross Russell invited Weinstock to come to the Dial session where “Embraceable You” and “Don’t Blame Me” were recorded, and it was there that he met Miles. At that session, it occurred to Weinstock that he could record bebop and maybe sign some of the rising stars: “I couldn’t get Bird, and Dizzy was tied up with RCA. But Miles and Lee Konitz, they could be the Bird and Dizzy of the future.” Weinstock asked Miles to have a drink with him after the session, but when Miles said he’d rather have ice cream, they went out for ice cream.

It was an odd relationship, this bebop recording business. The big record companies wanted nothing to do with marginal music and low sales, much less to contend with junkies and musical eccentrics. But the small labels took chances, putting up with the craziness, documenting a new art form in the making, in return paying as little as possible and tying the musicians to long-term contracts, and — like the rest of the recording business — paying for recording expenses out of the musicians’ earnings. Weinstock once offered this glimpse of his dealings with Davis:

“We’d get into these staring sessions. He’d ask for more money, and I wouldn’t answer. Then, I’d look at him and he’d look at me; we’d just stand there. We went through this a lot. I’d give him the money, but I’d always say, “Okay, that means we have to do another album.” He’d say, “I don’t want to do another album.” I’d say, “And I want better people than the last!” So that’s how those sessions with Milt Jackson and Monk came about. Those were some of our best sessions, because before he’d get the money — this was part of the game — I’d make him think real hard about who he was going to get.”

It was cockroach capitalism, filled with potential for strife and resentment of all kinds, compounded by whites owning the companies and blacks by and large supplying the music. It was business as usual, only worse.

Another “too deep” to be true deep groove. .At least, we have the back cover pictured…

http://www.ebay.com/itm/LEE-MORGAN-CANDY-BLUE-NOTE-ORIGINAL-DEEP-GROOVE-MONO-NM-JAZZ-LP-/380606901525?pt=Music_on_Vinyl&hash=item589df06d15

Michel-could you please put comments such as this in the reader forum section? That’s really where it will be seen by all,whereas this entry deserves a reply on it’s own merits. Thanks.

done

Funny, I used that Miles quote in my final research paper for my BA. Truly an interesting read, thanks for posting this.. the cover intrigues me as well.

From a french point of view, i’d say that even if this 10″ is rare, as are many barclay releases of the period, it has never been implied in any form of cult or ebay frenzy. It is visually very nice cover, no doubt, but I really can’t understand why this one fetched more thant 500 $. Here are some previous (and recent) auctions of this record :

http://www.auctionresults.eu/25CM-MILES-DAVIS-GROUP-QUINTET-84018-BARCLAY/370535625664.html

http://www.auctionresults.eu/MILES-DAVIS-25-CM-BARCLAY-RARE/120126585629.html

Regarding the picture, it was taken probably in 1948, and the author and location remain unknown. It originally comes from the Francis Paudras collection.

http://www.jazzhouse.org/gone/lastpost2.php3?edit=920558424.

It is featured in many Miles related book, without any credits, and always linked with the “Birth of the Cool” era. I think this is pure speculation to see this picture as an illustration of a young Miles high on drugs.

I think that all Miles Davis prestige 10 inch sessions were also released on french barclay. I do not own this copy ( which must be the equivalent to PRLP 124 ) but a few others. They usually are heavy pressings that carry the original prestige matrix and (if the recording was mastered by van Gelder) RVG hand etched in the dead wax. I checked this for barclay 84037 / PRLP 182. This might indicate that the barclay issues were pessed using the original stampers. Until now the barclay pressings were an opportunity to find a nice recording at a reasonable price ( 20-50 Euro ) This might have changed now.